jueves, 16 de mayo de 2024

jueves, 9 de mayo de 2024

Paya Frank .- Origen del Conflicto Israel - Palestino

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1q9j2m2_39iW9wkbt4IMVfp-0VtLWNYce/view?usp=sharing

miércoles, 8 de mayo de 2024

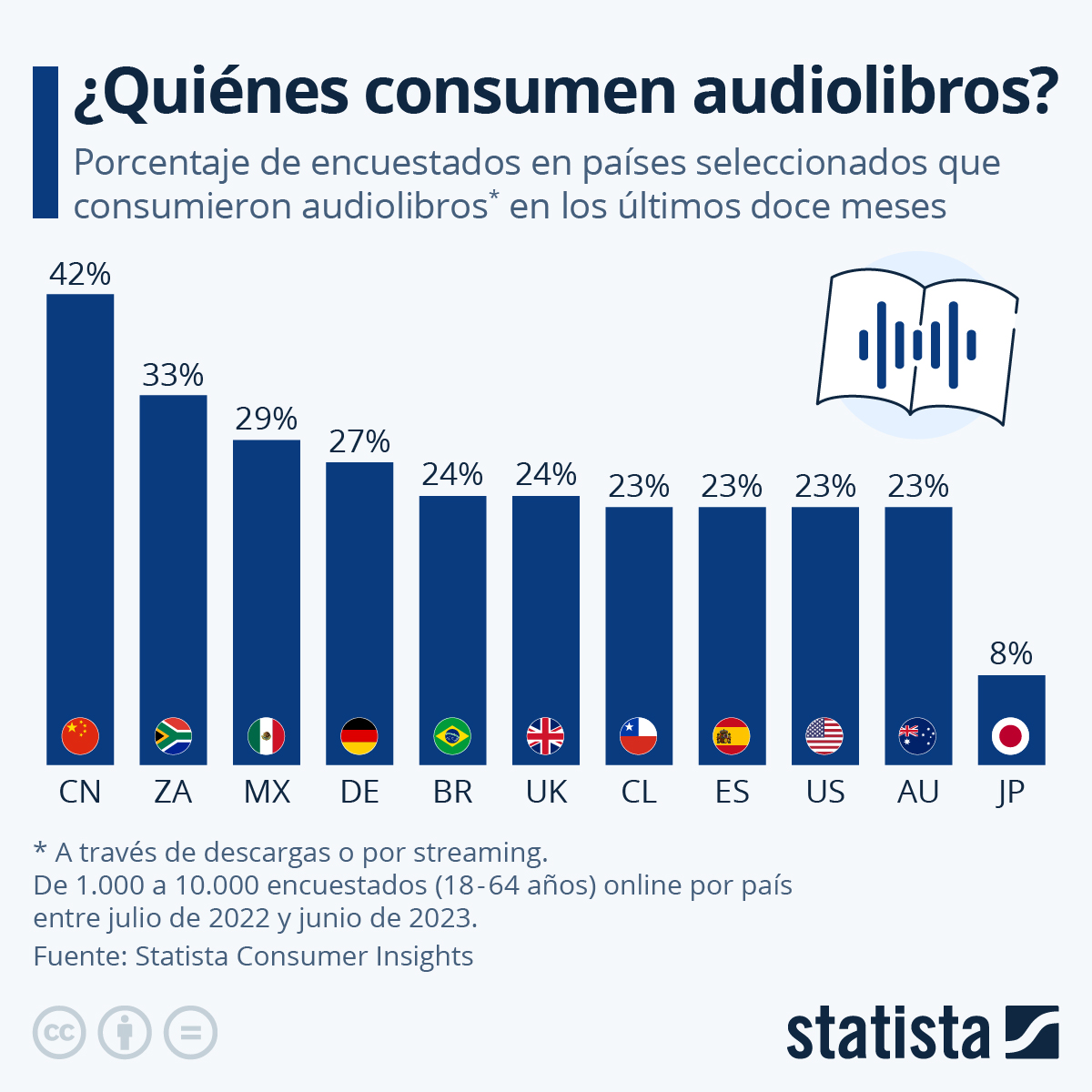

¿Quiénes consumen audiolibros?

Melo, María Florencia Melo. Infografía: ¿Quiénes consumen audiolibros? Statista Daily Data [en línea], 2023. [consulta: 3 mayo 2024]. Disponible en: Spotify ha anunciado que a partir de hoy, los usuarios de cuentas premium en el Reino Unido y Australia podrán disfrutar de hasta 15 horas de audiolibros, con una selección de aproximadamente 150.000 títulos incluidos en el plan. Se espera que Estados Unidos también tenga acceso a este beneficio a finales de este año, seguido probablemente por otros mercados. Según datos de la macroencuesta Statista Consumer Insights, en China, el 42% de los encuestados han consumido audiolibros en los últimos doce meses, seguido de cerca por Sudáfrica con un 33%. México y Alemania muestran un porcentaje considerable de consumidores de audiolibros, con un 29% y 27%, respectivamente. Por otro lado, Brasil, el Reino Unido, Chile, España, Estados Unidos y Australia presentan porcentajes similares, todos alrededor del 23% o 24%. Por último, Japón tiene el porcentaje más bajo de consumidores de audiolibros entre los países analizados en el gráfico, con solo un 8%. |

THE ABYSS Leonidas Andreiev

The day was

drawing to a close, but the young couple continued to walk and talk, paying no

attention to the time or the road. In front of them, in the shade of a tree,

stood the dark mass of a grove, and among the branches of the trees, like

burning coals, the sun burned, inflaming the air and transforming it into

glittering golden dust. The sun appeared so close and luminous that everything

seemed to vanish; He alone remained, and painted the road with his own crimson

tints. It hurt the eyes of passers-by, who turned their backs, and suddenly

everything that fell within their field of vision was extinguished, it became

the tall trunk of a fir tree that shone through the greenery like a candle

in peaceful

and clear, and small and intimate. A little farther away, a short mile away,

the red one set in a darkened room; The reddish glow of the road stretched

before them, and every stone cast its long black shadow; and the girl's hair,

bathed in the rays of the sun, now shone with a golden nimbus. A loose hair,

separated from the rest, fluttered in the air like a golden thread woven by a

spider.

The first

shadows of dusk did not interrupt or change the course of their conversation.

It went on as before, intimate and quiet; He went on to discuss the same theme:

the strength, beauty, and immortality of love. They were both very young; The

girl was not more than seventeen years old; Ncmovctsky had just turned

twenty-one. They both wore student uniforms: she in the modest brown dress of a

female school student, her companion in the elegant attire of a technology

student. And, like their conversation, everything around him was young,

beautiful, and pure. Their figures, erect and supple, advanced with a light,

elastic step; Their cool voices, uttering even the most vulgar words with

thoughtful tenderness, were like a rivulet on a quiet spring night, when the

snow has not yet quite melted on the mountainsides.

They

walked, rounding the bend of an unknown road, and their long shadows, with

absurdly small heads, now advanced separately, now emerged together in a long,

narrow strip, like the shadow of a poplar. But they did not see the shadows,

for they were too absorbed in their talk. As he spoke, the young man did not

take his eyes off the girl's beautiful face, over which the setting sun seemed

to have left a measure of its delicate tints. As for her, she bent her eyes

over the path, pushing aside the tiny pebbles with the tip of her parasol, and

watched now one foot, now the other, as they emerged from under her dark dress.

The path

was interrupted by a dusty ditch with footprints imprinted on them. For a

moment, the two young men stopped. Zinochka raised his head, looked about him

with a puzzled air, and asked:

"Do

you know where we are?" I had never been here.

His

companion carefully examined their surroundings.

-Yes, I

know. There, behind the hill, is the city. Give me your hand. I'll help you

cross.

He

stretched out his hand, white and thin as a woman's, not marred by hard work.

Zinochka was cheerful. She wanted to leap over the ditch by herself, and run,

crying, "Get me, if you can!" But he restrained himself, bowed his

head with modest gratitude, and timidly stretched out his hand, which retained

its childish morbidity. Nemovetsky felt the urge to squeeze the trembling

little hand tightly, but she restrained herself too, and with a slight bow she

took it politely in hers and modestly turned her head when, as she crossed the

ditch, the girl flashed her calf fleetingly.

And again

they walked and talked, but their thoughts were filled with the momentary touch

of their hands. She could still feel the dry warmth of the palm and the strong

male fingers; He felt pleasure and shame, while he was conscious of the

submissive softness of the tiny female hand, and saw the black outline of her

foot and the little shoe that wrapped around him tenderly. He was overcome by a

sudden desire to sing, to stretch out his hands to the sky, and to shout,

"Run! I want to you!", that ancient formula of primitive love among

the woods and the noisy waterfalls. And tears flowed down her throat from all

these desires.

The long

shadows vanished, and the dust on the road turned gray and cold, but they

didn't notice and continued chatting. They had both read many good books, and

the radiant images of men and women who had loved, suffered, and perished out

of pure love stood before them. His memoirs resurrected fragments of almost

forgotten verses, adorned with the melodious harmony and sweet sadness that

love provides.

"Do

you remember where this is from?" Nemovetsky asked, reciting: "...

Once again she is with me, she, whom I love; of whom, having never spoken, I

conceal all my sadness, my tenderness, my love..."

"No,"

replied Zinochka, and repeated thoughtfully, "All my sadness, my

tenderness, my love..."

"All

my love," Nemovetsky replied like an echo.

Other

memories came back to them. They remembered those girls, pure as lilies, who,

dressed in black, sat alone in the park, ruminating on their sorrow among the

dead leaves, but happy in the midst of their sorrow. They also remembered the

men who, abounding in will and pride, implored the love and delicate compassion

of women. The images thus evoked were sad, but the love reflected in that

sadness was radiant and pure. As vast as the world, as bright as the sun, it

lifted up fabulous beauty before his eyes, and there was nothing so powerful or

so beautiful on the face of the earth.

"Could

you die for love?" Zinochka asked, as she looked at his childish hand.

"Yes,

I might," replied Nemovetsky, convinced, and looked his companion in the

eye. And you?

-Yes, me

too. The girl thought thoughtfully. Dying for love is a joy.

Their eyes

met. Clear, limpid eyes, full of goodness. His lips smiled.

Zinochka

stopped.

"Wait

a minute," he said. You've got a thread in your jacket.

The girl

raised a hand to the young man's shoulder and carefully, with two fingers,

grasped the thread.

-That's it!

-Cried-. And, becoming serious, she asked, "Why are you so pale and

thin?" You study too much...

"And

you have blue eyes, with golden sparks," replied Nemovetsky, looking into

the girl's eyes.

"And

yours are black. No, chestnut trees. They seem to shine. There are in them...

Zinochka

didn't finish the sentence. He turned his head, his cheeks flushed, his eyes

took on a shy expression, while his lips smiled involuntarily. Without waiting

for Nemovetsky, who was also smiling with secret pleasure. The girl started

walking, but soon stopped.

"Look,

the sun has set!" He exclaimed in sorrowful astonishment.

"Yes,

it has been set," replied the young man with a new sadness.

The light

had faded, the shadows had died, everything was pale, dying. At that point on

the horizon where the sun had burned, dark masses of clouds were now silently

accumulating, conquering blue space step by step. The clouds gathered, pushed

each other, slowly transformed their monstrous profiles; They were advancing,

as if driven against their will by some terrible, implacable force.

Zinochka's

cheeks grew paler and her lips redder; His pupils widened imperceptibly,

obscuring his eyes. Whispered:

-I'm

scared. I am concerned about the silence that surrounds us. Have we gone

astray?

Nemovetsky

knitted her bushy eyebrows and looked around.

Now that

the sun had disappeared and the approaching night breathed fresh air,

everything seemed cold and inhospitable. The grey field stretched out on either

side with its stunted grass, its hills and its hollows. There were many of

these hollows, some deep, some small, and full of vegetation; the silent

darkness of night had already crept into them; And because of the existence of

signs of cultivation, the place seemed even more desolate.

Nemovetsky

crushed the feeling of insecurity that was struggling to invade him and said:

"No,

we haven't gone astray. I know the way. First to the left, then through that

grove. Are you scared?

She smiled

bravely and replied:

"No.

Not now. But we need to get home early and have some tea.

They

quickened their pace, only to shorten it again at once. They did not look by

the wayside, but they could feel the indolent hostility of the tilled field,

which surrounded them with a thousand tiny motionless eyes, and the sensation

drew them nearer to each other and awakened in them memories of childhood.

Bright memories, full of sun, green foliage, love and laughter. It was as if

this had not been a life, but an immense and melodious song, and they

themselves had been part of that song as sounds, as two faint notes: one clear

and resonant like pure crystal, the other somewhat duller but more animated at

the same time, like a small bell.

Signs of

human life began to appear. Two women were sitting on the edge of a hollow. One

of them was cross-legged and staring into the bottom of the hole. He lifted his

head, touched with a handkerchief, from which tufts of matted hair escaped. She

wore a very dirty blouse with flowers printed on it, as big as apples; Her

laces were loose. He didn't look at those passing by. The other woman was very

close, half reclining, with her head thrown back. He had a broad, coarse face,

with the features of a peasant, and under his eyes the prominent cheekbones

showed two reddish spots, resembling very recent scratches. She was even

dirtier than the first woman, and she looked shamelessly at the two young men.

When these had passed, the woman began to sing in a strong, masculine voice:

"For

you alone, my beloved, I will burst like a flower..."

"Varka,

did you hear?" The woman turned to her silent companion and, receiving no

answer, burst into hoarse laughter.

Nemovetsky

had known such women, who were filthy even when wearing luxurious dresses; He

was used to them, and now they slipped from his retina and vanished, leaving no

trace. But Zinochka, who had almost brushed against them in her modest dress,

felt that something hostile invaded her soul. But in a few moments the

impression had vanished, like the shadow of a cloud rushing across the flowery

meadow; and when, advancing in the same direction, a barefoot man passed by,

accompanied by another of these women, Zinochka saw them, but paid no attention

to them.

And once

more they walked and talked, and behind them moved reluctantly a dark cloud,

casting a transparent shadow. The darkness gradually thickened. Now, the two

young men were talking of those terrible thoughts and sensations that visit man

during the night, when he cannot sleep and all is silence around him; when the

darkness, immense and endowed with multiple eyes, is crushed against his face.

"Can

you imagine the infinite?" Zinochka asked, putting a hand to his forehead

and closing his eyes.

"The

infinite?" "No," replied Nemovetsky, closing his eyes as well.

"Sometimes

I see it. I first noticed it when I was very young. Imagine a large number of

cards. One, another, another, endless letters, an infinite number of letters...

It's terrible!

Zinochka

trembled.

"But

why letters?" Nemovetsky smiled, though he felt uncomfortable.

-I don't

know. But I saw letters. One, another... endless.

The

darkness was thickening. The cloud had already passed over their heads, and

standing in front of them he could now see the faces of the two young men,

growing paler and paler. The ragged figures of other women like the ones they

had encountered appeared more frequently; as if the deep hollows, dug for some

unknown purpose, were vomiting them to the surface. Now alone, now in groups of

two or three, they appeared, and their voices echoed noisily and strangely

desolate in the still air.

"Who

are these women?" Where do they come from? Zinochka asked in a low,

trembling voice.

Nemovetsky

knew what kind of women these were. He was terrified that he had fallen into

this wicked and dangerous neighbourhood, but he answered calmly:

-I don't

know. It doesn't matter. Let's not talk about them. We'll be home soon. We just

have to go through that grove and we will reach the city. Too bad we came out

so late.

The girl

found those words absurd. How could he say they had left late, if it was only

four o'clock? He looked at his companion and smiled. But Nemovetsky's brows

continued to furrow, and, to reassure and comfort him, Zinochka suggested:

"Let's

go faster." I want to have some tea. And the grove is very close now.

"Yes,

we're going to go faster.

When they

entered the grove and the silent trees came together in an arc above their

heads, the darkness grew more intense, but the atmosphere was also more

peaceful and calm.

"Give

me your hand," Nemovetsky proposed.

She shook

his hand, with some hesitation, and the faint touch seemed to light up the

darkness. Their hands didn't move or squeeze each other. Zinochka even pulled

away from his partner a bit. But all his consciousness was focused on the

perception of the tiny place in the body where the hands touched. And again

came the desire to talk about the beauty and mysterious power of love, but to

speak without violating silence, to speak, not through words but through looks.

And they thought they ought to look, and they wished they would, but they dared

not...

"And

there are some people here!" Zinochka exclaimed cheerfully.

On the bald

spot, where it was brighter, three men sat by an almost empty bottle, silent.

They looked expectantly at the newcomers. One of them, clean-shaven like an

actor, laughed loudly and whistled provocatively.

Nemovetsky's

heart beat with a trepidation of horror, but, as if pushed from behind, he

walked on in the direction of the trio, sitting by the roadside. There they

were waiting, and three pairs of eyes were staring at the passers-by,

motionless and threatening.

Desirous of

winning the goodwill of these idle and ragged men, in whose silence he

perceived a threat, and of gaining their sympathy through his own helplessness,

Nemovetsky asked:

"Is

this the road that leads to the city?"

They didn't

answer. The clean-shaven whistled something mocking and indefinable, while the

others remained silent and stared at the pair with malignant intensity. They

were drunk, hungry for women and sensual fun. One of the men, with a reddish

face, stood up like a bear and sighed heavily. His companions glanced at him,

and then fixed their intense gaze on Zinochka again.

"I'm

terribly afraid," whispered the girl.

Nemovetsky

did not hear his words, but he could sense them by the weight of the arm

resting on him. And, trying to appear calm that he did not feel, though

convinced of the irrevocability of what was about to happen, he went on with

studied firmness. Three pairs of piercing eyes drew nearer and nearer,

twinkled, and were behind him.

"It's

better to run," thought Nemovetsky. And he said to himself, "No, it

is better not to run."

"It's

a chick!" Are you afraid of him? said the third member of the trio, a bald

man with a sparse red beard. And the girl is very fine. May God grant that we

may give each of us one like her!

The three

men burst out laughing.

-Hey! One

minute! I want to talk to you, horseman! The taller man shouted in a strong

voice, looking at his comrades.

The trio

rose to their feet.

Nemovetsky

walked on, without turning.

-Stop when

asked! The redhead exclaimed. And if you don't want to, face the consequences!

"Is he

deaf?" The taller man growled, and in two strides he approached the pair.

A massive

hand fell on Nemovetsky's shoulder and swung him around. As he turned, he found

very close to his face the round, bulging, terrible eyes of his assailant. They

were so close that he seemed to see them through a magnifying glass, and he

could clearly distinguish the small red veins in the eyeball and the yellowing

of the eyelids. He dropped Zinochka's hand and, sinking his own into his

pocket, murmured:

"Do

you want money?" I can gladly give you the one I'm carrying.

The bulging

eyes flashed. And when Nemovetsky looked away from them, the tall man gained

momentum and slapped the young man's chin. Nemovetsky's head was thrown back,

his teeth cracked, and his cap fell to the ground; Waving his arms, the young

man collapsed heavily. Silently, without uttering a single cry, Zinochka turned

and ran with all the speed he was capable of. The man with the clean-shaven

face uttered an exclamation that rang strangely:

-A-a-ah!

And he

started running after Zinochka.

Nemovetsky

sprang to his feet, but had barely regained his vertical when another blow to

the back of the head knocked him down again. There were two of his adversaries,

and the young man was not accustomed to physical combat. Yet she struggled for

a long time, scratched with her nails like a whitewashed woman, bit with her

teeth, and sobbed in unconscious despair. When he was too weak to continue

resisting, the two men lifted him off the ground and pushed him out of the way.

The last thing he saw was a fragment of the red beard that almost touched his

mouth, and beyond that, the darkness of the forest and the light-colored blouse

of the fleeing girl. Zinochka ran silently and swiftly, as he had run a few

days before when they were playing marro; And behind her, with short strides,

gaining ground, ran the clean-shaven man. Then, Nemovetsky noticed the

emptiness around him, his heart stopped beating as the young man experienced

the sensation of sinking into a bottomless pit, and finally tripped over a

stone, hit the ground, and lost consciousness.

The tall

man and the red-haired man, having thrown Nemovetsky into a ditch, paused for a

moment to listen to what was happening at the bottom of the ditch. But their

faces and eyes were turned to one side, in the direction taken by Zinochka.

From there the girl's shrill cry rose, only to die out almost immediately. The

tall man muttered angrily:

"The

very pig!"

Then,

rising up like a bear, he ran.

-Me too! Me

too! His red-haired comrade shouted, running after him. He was weak and

panting; He had hurt his knee in the fight, and he was furious at the thought

that he had been the first to see the girl and would be the last to have her.

He stopped to rub his knee; then, putting a finger to his nose, he sneezed, and

ran again, crying, "Me too!" Me too!

The dark

cloud dissipated across the sky, fading into the still night. The short-cut

figure of the red-haired man was soon swallowed up by the darkness, but for a

time the uneven rhythm of his footsteps, the rustling of fallen leaves on the

ground, and the plaintive cries could be heard:

-Me too!

Brethren, so am I!

Nemovetsky's

mouth was full of dirt. When he came to, the first sensation he experienced was

the awareness of the pungent and pleasant smell of the earth. His head was

heavy, as if it were full of lead; I could barely turn it back. His whole body

ached, especially his shoulder, but he didn't have any broken bones. He sat up,

and for a long time looked over him, neither thinking nor remembering. Directly

above his head a bush bent its broad leaves, and between them the now clear sky

was visible. The cloud had passed, not dropping a single drop of rain, and

leaving the air dry and exhilarating. Very high, in the middle of the sky,

appeared the sculpted moon, with transparent edges. He was living his last

nights and his light was cold, discouraged, lonely. Small tufts of clouds

glided swiftly across the heights, pushed by the wind; They did not obscure the

moon, merely caressing it. The solitude of the moon, the timidity of the

fugitive clouds, the barely perceptible breath of the wind below, made one feel

the mysterious depth of the night dominating over the earth.

Nemovetsky

suddenly remembered everything that had happened, and could not believe that it

had happened. It was all so terrible that it didn't seem true. Could the truth

be that horrible? He, too, sitting on the ground in the middle of the night and

looking at the moon and the patches of receding clouds, felt strange to

himself, so much so that he thought he was living through a vulgar but terrible

nightmare. These women, of whom he had known so many, had also become a part of

the dreadful and perverse dream.

"It

can't be! He exclaimed, shaking his head weakly. It can't be!"

He

stretched out an arm and began to reach for his cap. When he couldn't find her,

everything became clear to him; And he realized that what had happened had not

been a dream, but the horrible truth. Possessed with terror, he clung furiously

to the walls of the ditch trying to get out of it, only to find himself again

and again with his hands full of dirt, until finally he managed to cling to a

bush and climb to the surface.

Once there,

he ran without choosing a direction. For a long time he kept running, circling

among the trees. The branches scratched his face, and again it all began to

look like a dream. Nemovetsky experienced the sensation that something like

this had happened to him before: darkness, invisible branches of the trees, as

he ran with his eyes closed, thinking it was all a dream. Nemovetsky stopped,

and then sat down in an awkward posture on the ground, without any elevation.

And again he thought of his cap, and murmured:

"This

is: I have to kill myself. Yes, I have to kill myself, even if this is a

dream."

He sprang

to his feet, but remembered something and started walking slowly, trying to

locate in his confused brain the place where they had been attacked. It was

almost pitch black in the forest, but now and then a moonbeam filtered through

the branches of the trees, deceiving him; It lit up the white trunks, and the

forest seemed to be filled with motionless and mysterious silent people. All

this, too, seemed like a fragment of the past, and it seemed like a dream.

"Zinaida

Nikolaevna!" called Nemovetsky, uttering the first word aloud and the

second in a low voice, as if the loss of her voice had also given up all hope

of an answer. No one answered.

Then

Nemovetsky found his way, and recognized it immediately. He arrived at the

calvery. And when he got there, he realized that everything had really

happened. In his terror, he ran, crying out:

"Zinaida

Nikolaevna! Soy yo! No!"

No one

answered his call. Taking the direction in which he thought the city was, he

shouted with all the force that remained in his lungs:

«¡S o c o r

r o o o!»

• Again he

ran, whispering something as he brushed the bushes, until a white spot appeared

before his eyes, like a spot of frozen light. It was Zinochka's prostrate body.

"Oh!

My god! What is this?" said Nemovetsky, his eyes dry, but his voice

sobbing. He dropped to his knees and came into contact with the girl lying

there.

His hand

fell on the naked body, which was soft to the touch, and firm, and cold, but

not dead. Trembling, Nemovetsky ran his hand over her.

"My

dear, darling, it's me," she whispered, searching for the girl's face in

the darkness.

Then he

stretched out a hand in another direction, and again came into contact with the

naked body, and wherever he rested his hand touched the woman's body, so soft,

so firm, seeming to acquire warmth at the touch of his hand. Nemovetsky

suddenly drew her hand away, and immediately rested it again on that body,

which she could not associate with Zinochka. Everything that had happened here,

everything that those men had done with this mute woman's body, appeared to

Nemovetsky in all its frightful reality, and she found a strange and eloquent

answer in her own body. With his eyes fixed on the white spot, he raised his

eyebrows like a man engaged in the task of thinking.

"Oh!

My god! What is this?" he repeated, but the sound came unreal, deliberate.

Nemovetsky

laid her hand on Zinochka's heart: it was beating faintly but steadily, and

when the young man leaned over the woman's face he caught the faint breath as

well. The girl seemed to be in a peaceful sleep. He called to her in a low

voice:

"Zinochka!

It's me!"

But he knew

immediately that he wouldn't want to see her awake until a long time had

passed. Nemovetsky held her breath, glanced furtively around, and then stroked

the girl's cheek; First he kissed her closed eyes, then her lips... Fearing

that he would wake up, he leaned back and remained in an icy attitude. But the

body was motionless and mute, and in its helplessness and easy access there was

something pitiful and exasperating. With infinite tenderness Nemovetsky tried

to cover the girl with the pieces of her dress, and the double consciousness of

the cloth and the naked body was as sharp as a knife and as incomprehensible as

madness. Here, wild beasts had feasted: Nemovetsky caught the fiery passion in

the air and dilated her nostrils.

"It's

me! It's me!" he repeated like a madman, not understanding his

surroundings and still possessed by the memory of the white selvedge of the

woman's skirt, the black silhouette of the foot, and the footwear that so

tenderly contained it. As he listened to Zinochka breathe, his eyes fixed on

his face, he waved a hand. He stopped to listen, and waved his hand again.

"What

am I doing?" he cried aloud in despair, and leaned back, horrified at

himself.

For an

instant, Zinochka's face flashed in front of him and vanished. He tried to

comprehend that this body was Zinochka, with whom he had been walking and

talking about the infinite, but he could not comprehend. He tried to feel the

horror of what had happened, but the horror was too intense to grasp.

"Zinaida

Nikolaevna! He cried imploringly. What does this mean? Zinaida

Nikolaevna!"

But the

tormented body remained mute, and, continuing his mad monologue, Nemovetsky

dropped to his knees. He pleaded, threatened, said he would commit suicide, and

grabbed the prostrate body, pressing it against his...

The body

made no resistance, obedient meekly to his movements, and the whole thing was

so terrible, incomprehensible, and savage that Nemovetsky sprang to his feet

again and cried out sharply:

"Help!"

But the

sound was fake, as if it were deliberate.

And once

more she dropped upon the passive body, with kisses and tears, feeling the

presence of an abyss, a dark, terrible, absorbing abyss. There was no

Nemovetsky there; Nemovetsky had been left behind, somewhere, and the being who

had replaced him was now shaking the warm, submissive body, and was saying with

the cunning smile of a madman:

"Answer

me! Or don't you want to answer me? I love you! I love you!"

With the

same sly smile he brought his wide eyes to Zinochka's face and whispered:

"I

love you! You don't want to talk, but you're smiling, I notice. I love you! I

love you! I love you!"

He pressed

Zinochka's body tighter against his, and his passivity aroused a savage

passion. Wringing her hands, Nemovetsky whispered again, her voice hoarse:

"I

love you! We won't tell anyone, and no one will know. I'll marry you tomorrow,

whenever you want. I love you! I'll kiss you, and you'll answer me, yes?

Zinochka..."

He pressed

his lips to hers, and in the anguish of that kiss his reason was utterly

nullified. It seemed to him that Zinochka's lips quivered. For an instant,

horror cleared his mind, opening a black abyss before him.

And the

black abyss engulfed him.

The

end